Some people have recommended that the statue of Jefferson Davis be removed from the rotunda of the Kentucky state capitol. I would like to present an alternate option that does more credit to our great Commonwealth. The matter is currently under review by the Kentucky Historic Properties Advisory Commission. They recently called for public comment in advance of their deliberations.

The objection to Davis’ presence is understandable, but I think there is an opportunity to bring a higher purpose to the statues in the capitol rotunda. It can be a place of education and restoration, and the full-telling of Kentucky’s unparalleled history and mark on the United States (especially the story of American slavery, statesmanship, and reconciliation).

The story is larger than Davis

The key is to look at three statues which stand there as integral components of a single story. I am referring not only to Jefferson Davis, but to Abraham Lincoln and Henry Clay.

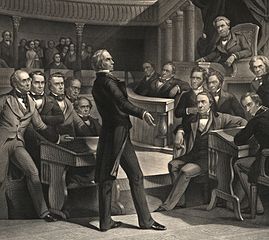

I don’t need to describe Lincoln’s monolithic role in the story, but it is useful to look again at Henry Clay, whose inscription in the rotunda calls him “Kentucky’s favorite son.”

For the first half of the 19th century, Kentucky offered to the United States its “favorite son,” who worked tirelessly for compromise, and to preserve the Union. He concluded one of his speeches in February, 1850 with these words: “I implore, as the best blessing which heaven can bestow upon me on earth, that if the direful and sad event of the dissolution of the Union shall happen, I may not survive to behold the sad and heartrending spectacle.”

For the first half of the 19th century, Kentucky offered to the United States its “favorite son,” who worked tirelessly for compromise, and to preserve the Union. He concluded one of his speeches in February, 1850 with these words: “I implore, as the best blessing which heaven can bestow upon me on earth, that if the direful and sad event of the dissolution of the Union shall happen, I may not survive to behold the sad and heartrending spectacle.”

Clay was granted his desire to be spared the sight of dissolution: He died before his fellow Americans chose to break the Union and go to war. Americans on both sides rejected Kentucky’s finest orator and call to civility and compromise. They chose instead Kentucky’s alternative offering: Two leaders to take them to the brink of destruction.

Do Kentuckians know why they identify as ‘Southern?’

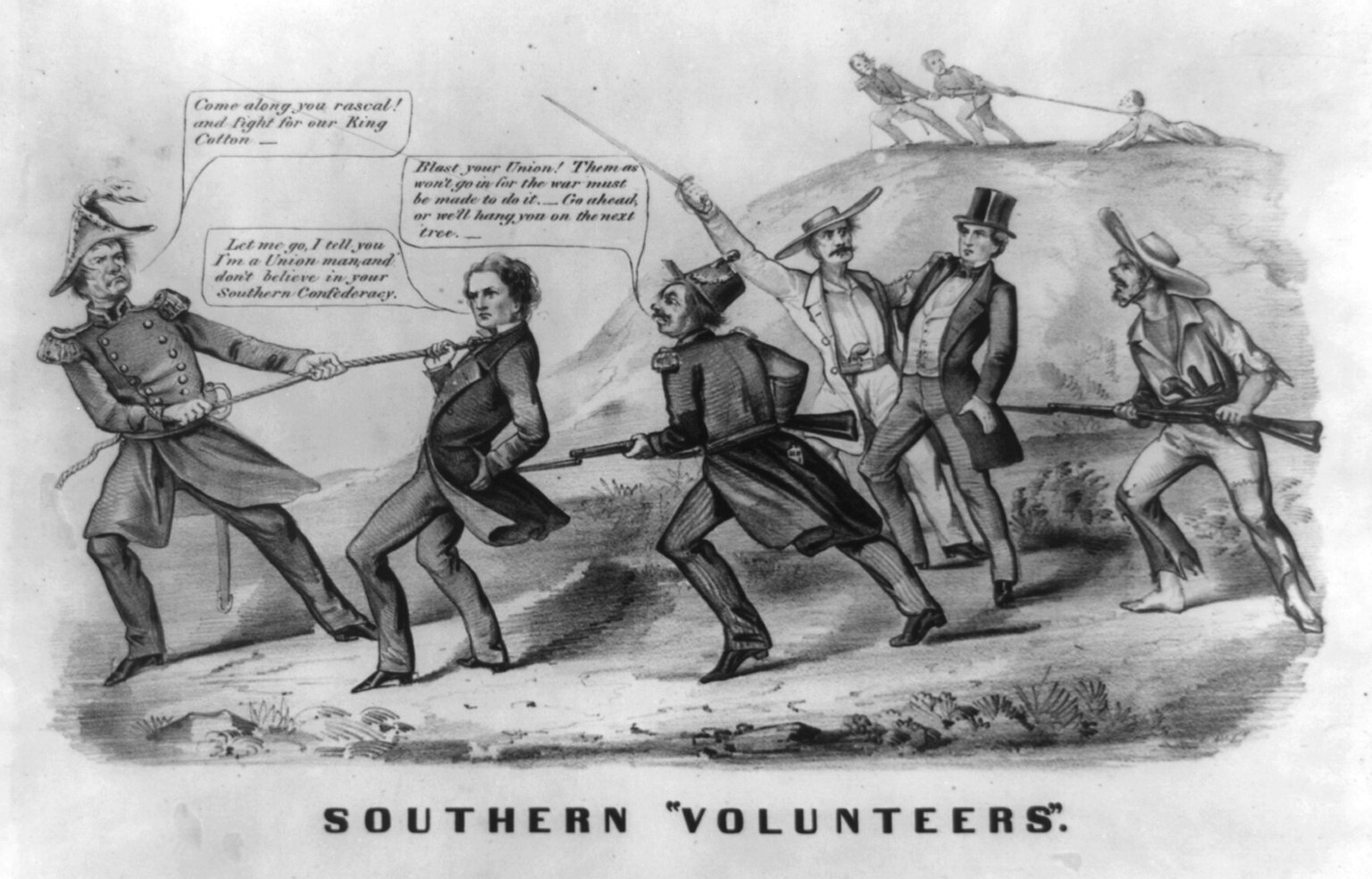

The Kentucky Historical Society’s “Civil War Governors” project (among others) reveals a great deal about the horror of war as it raged across the state and renegades murdered Kentuckians and pillaged and burned their subsistence. Kentucky reaped the folly of the nation, and paid the price for the evil of slavery. Clay’s previous efforts and the legislature’s vote to remain neutral were not enough to spare this state the depredation visited on the South.

The bitter memory of the Civil War helped drive “Lost Cause” sentiment in the early part of the 20th century, the period during which the Davis statue was erected in our rotunda. The “Lost Cause” myth perpetuated several ideas that still exist today: The Confederates were right and only lost because of some misfortune, and other embellishments about the South.

So, my rationale for keeping the Davis statue in the rotunda is based on two educational threads that can be put in place to enrich Kentuckians in that space: 1. Davis is part of a continuum of Kentuckians as American statesmen who dealt with the problem of slavery. 2. The existence of the statue itself is part of Kentucky’s story of slavery, Civil War, Reconstruction, culminating in the rise of the Lost Cause movement.

Davis is not heroic

I do have a caveat, though. One aspect of the Davis statue bothers me: The inscription reads “patriot, hero, statesman.” Modifying that characterization would be appropriate, because his legacy as a patriot or heroic leader is dubious. Here are two small examples:

1. Davis’ leadership style was terrible. In Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson gives this description: Davis “was not free himself from the sins of excessive pride and willfulness…Davis lacked Lincoln’s ability to work with partisans of a different persuasion for the common cause. Lincoln would rather win the war than an argument; Davis seemed to prefer winning the argument.” Among other decisions that rankled Confederate leaders, Davis recommended the first conscription law in American history.

1. Davis’ leadership style was terrible. In Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson gives this description: Davis “was not free himself from the sins of excessive pride and willfulness…Davis lacked Lincoln’s ability to work with partisans of a different persuasion for the common cause. Lincoln would rather win the war than an argument; Davis seemed to prefer winning the argument.” Among other decisions that rankled Confederate leaders, Davis recommended the first conscription law in American history.

2. Davis was also a miserable military strategist, and went through four secretaries of war in less than two years, because he used them as errand boys, rather than letting them manage the military. Russell Weigley’s book, A Great Civil War, explains how Davis thwarted Confederate success militarily. “The alternation between defense and attack in the West without consistent purpose was in part a product of the Confederacy’s lack of unified command. Jefferson Davis, proud of his military education and his military exploits in the Mexican War, persisted in being an active Commander in Chief and refused to appoint a professional leader for all the Confederate armies.”

Race and Reconstruction in Kentucky

Another factor in Kentucky’s Civil War legacy, is its Reconstruction (or “Readjustment”). There are few memorials or fully-developed educational locations devoted to the post-Civil War period. The horror of war was not quickly forgotten, and Kentuckians, unjustly, took their pain out on their black neighbors. According to Marion Lucas’ A History of Blacks in Kentucky, published by the Kentucky Historical Society, “In 1871 firing between blacks and whites broke out just after the polls closed in Frankfort, Paris, and Lexington.” This description is only one event in several years of intimidation and repression of black votes. The situation was dire enough that the U.S. Army built barracks in Frankfort and stationed troops there to protect the black population. That calamitous situation is memorialized by a lone historical marker near the extant barracks in Frankfort. (Learn more here.) Kentuckians would also benefit from a more robust and visible educational coverage of this period. It would help make sense of why so many Kentuckians consider themselves southern, and where the roots of our racial tension lay.

Conclusion

So, Davis’ statue should remain, because we must tell the whole truth about Kentucky. Clay, Lincoln, and Davis are the three-legged stool of that story. In the telling, we should also show Davis as he really was, and confront who we really are (and have been).

UPDATE:

The commission met today (August 5), and decided to leave the statue in the rotunda, and

“the panel voted to establish a committee that would determine ways to ensure the statues, including Jefferson Davis, are displayed in the appropriate historical context.”

(Here is the Governor’s statement.)

This blog post, incidentally, was the full-text of my comment, submitted to the commission during their call for public comments last month.