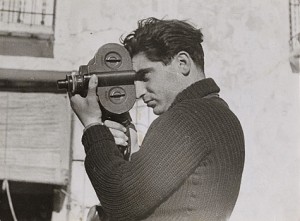

This morning I was sent a link to this article in The Atlantic, which describes a photo taken by war photographer Kenneth Jarecke at the end of Operation Desert Storm. The photo was not chosen for publication in the U.S., based on its graphic nature. This prompted me to examine more closely how Americans view death, in general, and wartime violence, in particular.

We are disconnected from death

It seems to me that Americans are disconnected from death, and dying. I attribute this in part to our high life-expectancy. These days, the average life-expectancy for Americans is about 78 years. Some data show that as recently as the turn of the 20th century the average life expectancy was 50 years. Infant and child mortality rates were also drastically higher in previous centuries. While vaccines, medical care, and standards of living have improved, disease, violence, and other depredations have decreased. Many American folk songs have extremely dark topics, for example, which gives just a small indication of what our ancestors experienced in the early growing phases of our society. Death was always around the corner.

It seems to me that Americans are disconnected from death, and dying. I attribute this in part to our high life-expectancy. These days, the average life-expectancy for Americans is about 78 years. Some data show that as recently as the turn of the 20th century the average life expectancy was 50 years. Infant and child mortality rates were also drastically higher in previous centuries. While vaccines, medical care, and standards of living have improved, disease, violence, and other depredations have decreased. Many American folk songs have extremely dark topics, for example, which gives just a small indication of what our ancestors experienced in the early growing phases of our society. Death was always around the corner.

Nancy Updike, a producer of the “This American Life” radio show, recently described her sudden realization of the modern disconnection with death. She had been present at her step-father’s death, and was amazed at the Hospice nurses who were present:

“I had never seen the kind of expertise these nurses had. They knew death. They seemed to understand it, whereas I, even though I had just watched someone fade away and die right in front of me, all I could think was, what just happened?”

Listen to her whole story here, where she explores death at an Hospice care facility: This American Life, episode 523

Is death part of war? If so, how should we deal with it?

So, back to the war photograph. In previous wars, most notably World War II, government censors ensured that the most violent and gruesome images were not presented to the American public. The press also voluntarily complied with censorship. This changed during the Vietnam War, when bloody scenes from the jungle were delivered to living room television sets. After Vietnam, while the military kept a tight reign on media presence on the battlefield, the censorship of Jarecke’s photo was not imposed by the military or the government, but by the American press itself.

So, back to the war photograph. In previous wars, most notably World War II, government censors ensured that the most violent and gruesome images were not presented to the American public. The press also voluntarily complied with censorship. This changed during the Vietnam War, when bloody scenes from the jungle were delivered to living room television sets. After Vietnam, while the military kept a tight reign on media presence on the battlefield, the censorship of Jarecke’s photo was not imposed by the military or the government, but by the American press itself.

The key idea presented in the Atlantic piece is that the expongement of human suffering from Gulf War journalism presented a view that it was a war of Hollywood explosions and no one really got hurt. Jarecke makes this excellent point:

“If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.”

We have progressed from government censorship, to journalistic self-censorship, to an inability to even process the idea of death. Think for a moment about how the American public responds to any sort of sudden, violent death: 9/11, Columbine, Sandy Hook, Islamic beheadings. These are all criminal acts, and unjustifiable, but Americans invariably respond with raw, untempered emotion. We are desensitized, we think that death is something that shouldn’t happen, and violent death is something we don’t understand.

Are we big enough to look at it?

I am not suggesting that we make death into something light, or devalue the loss of life. On the contrary, I think that only by understanding the actual gravity of death can we really know the consequences of our actions, as individuals, and as part of a nation which wages war.

Interesting post. I agree with you that the U.S. media definitely feels the need to sanitize war. While working on the copydesk of a newspaper during 9/11 and Desert Storm, I saw my share of gruesome war photos come across the wire, but those gruesome photos never made it into a paper. It seems, for many Americans it’s easier to process war and death when it’s only scenes of destroyed building or young children being helped — or like you say, a war of Hollywood explosions.

If you want another great book to read about war and death, read “This Republic of Suffering” by Drew Gilpin Faust. It’s a very well researched book and the author explores the U.S. Civil War and how the sheer number or deaths — and how the men died — forced a nation of survivors to reconcile reality with their long held belief of the “Good Death.”

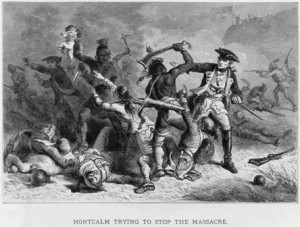

Excellent read, Zach. I know you are aware of the Matthew Brady photos from the Civil War. Those were very eye-opening to me — along with some of the video/stills from the D-Day invasion — and helped form my views on the last comment you make: The consequences of our actions as both an individual and part of a nation that wages war. Keep up the good work, although I must admit, some of the conversations you and Bryan have on Facebook go right over my head. But it’s like you guys were back in the office.

Charlie and Chuck: Interesting that you both thought of the Brady photos. Those images also made an impact on me. I wonder to what extent their black-and-white format softens their effect? But the main point, which Charlie makes, is that the ACW was the last time Americans have experienced Total War. This was the last time that coming face-to-face with war was unavoidable for us.

Thanks for the feedback!